Jul 01, 2020

Pandemic Exacerbates Racial Divide in Housing Crisis

The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Housing Crisis

New York City’s housing crisis has persisted for years, leading to overcrowding and homelessness, forced moves and evictions. 1 And consequences of this crisis have been overly borne by Black and Hispanic New Yorkers — a direct product of housing policy and gentrification, which have disproportionately pushed New Yorkers of color from their homes and served to concentrate and segregate poverty and material hardship in New York City. 2 The COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated housing insecurity — particularly for Black (non-Hispanic) and Hispanic New Yorkers who have lost work.

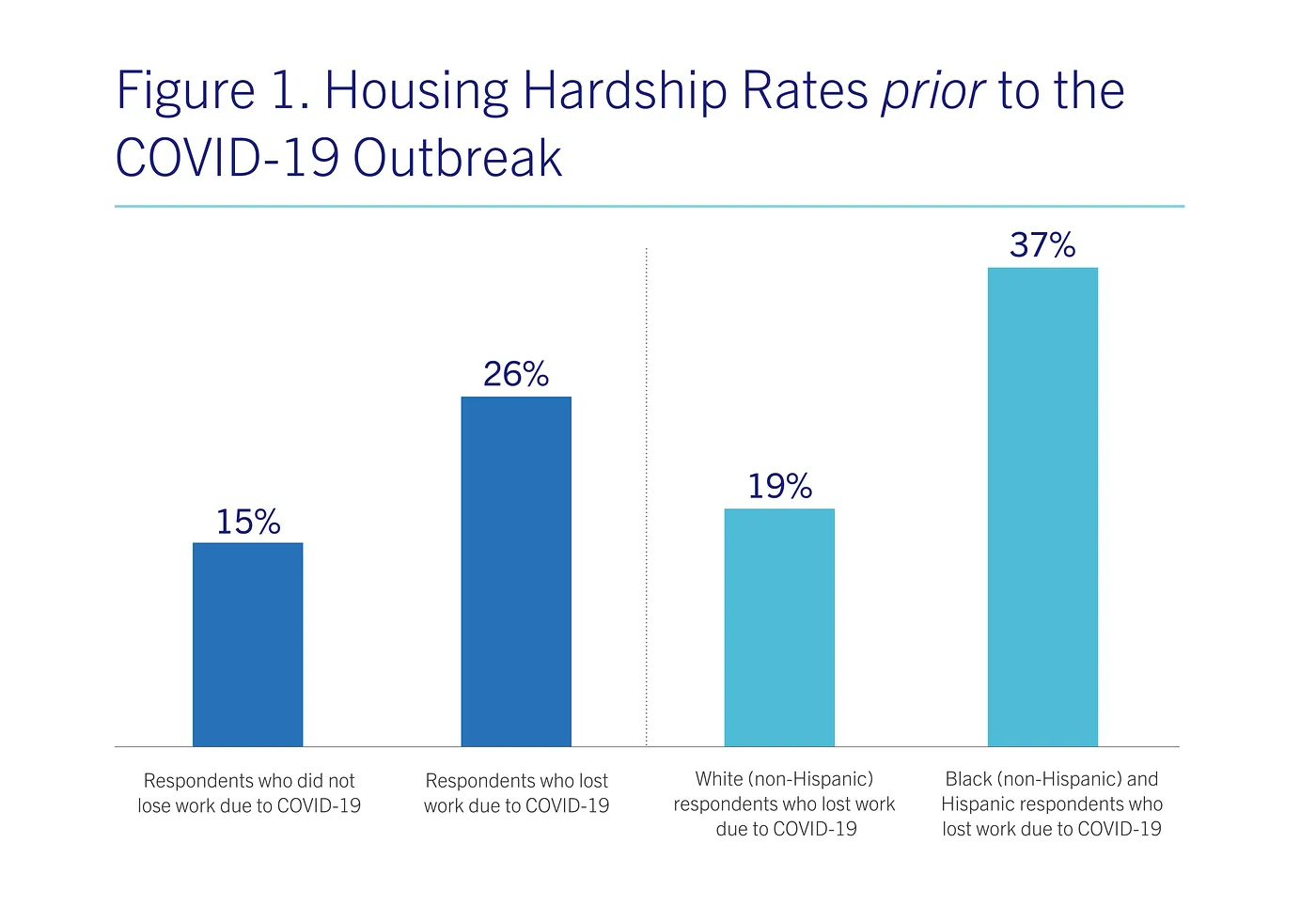

Preliminary data from the Poverty Tracker show that Black (non-Hispanic) and Hispanic workers who have lost work for a reason related to COVID-19 are significantly more likely to have faced housing hardship prior to the pandemic compared to White (non-Hispanic) workers who have lost work and to respondents who have not lost work. Overall, 26 percent of Poverty Tracker respondents who have lost work for a reason related to COVID-19 faced some form of housing hardship priorto the COVID-19 outbreak — compared to 15 percent of those respondents who have not lost work (see Figure 1). Looking at these results broken out by race and ethnicity, we find that 37 percent of Black (non-Hispanic) and Hispanic respondents who have lost work faced a housing hardship prior to the pandemic, compared to only 19 percent of White (non-Hispanic) respondents who have lost work. Black (non-Hispanic) and Hispanic respondents who lost work due to COVID-19 experienced housing hardship at nearly twice the rate of White (non-Hispanic) respondents who have lost work.

Housing hardship is defined as not being able to make a rent or mortgage payment, moving in with others because of financial problems, or staying in a shelter or other place not meant for regular housing.

New Yorkers who have been unable to make rent in the past are particularly vulnerable to eviction and forced moves, and the loss of employment and income associated with the pandemic has only heightened these vulnerabilities. Black (non-Hispanic) and Hispanic respondents who have lost work are therefore significantly more vulnerable to displacement for reasons related to the pandemic — a consequence that would be devastating for individuals and families, neighborhoods, and the city as a whole, and would exacerbate the effects of gentrification, including racial segregation and the concentration of economic disadvantage.

The Policy Response

In June, Governor Cuomo signed a $100 million rental assistance bill that will provide emergency vouchers for eligible individuals or families affected by COVID-19. The vouchers, which are paid directly to property owners, will cover three months of rent. The vouchers will cover the difference between monthly rent (up to 125 percent of Fair Market Rent) and 30 percent of eligible tenants’ new monthly adjusted income. This bill will help families afford rent and avoid eviction in the short run, which in turn helps landlords meet their mortgage and property tax obligations.

On June 30, the Governor signed the Tenant Safe Harbor Act (S.8192b/A.10290), which prohibits courts from issuing a judgment of possession or a warrant of eviction for the non-payment of rent against any tenant or lawful occupant who has suffered financial hardship during the COVID-19 emergency. The bill defines the end of the COVID-19 covered period as the point at which none of the Executive Orders and provisions restricting economic and social activity remain in effect. This flexible period is major extension of the current moratorium and ensures that those whose employment and income have been negatively affected by the pandemic and subsequent orders will have an opportunity to return to work before they are at risk of being forced from their home.

While these bills will help thousands of New Yorkers stay in their homes, they will do little to stabilize the city’s housing market. The Emergency Rental Assistance vouchers will only cover rent owed from April 1st through July 31st. Funds will expire just as Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) runs out, meaning eligible workers who have lost work or income due to COVID-19 will no longer receive $600 in weekly unemployment benefits. Additionally, while the Tenant Safe Harbor bill enables people to stay in their homes, it does not help them meet their housing costs; landlords are still permitted to seek monetary judgements against non-paying tenants. Come August, New Yorkers will still need substantial assistance to afford rent and landlords may struggle to meet mortgage and property tax payments.

To prevent a full collapse of the housing market, we need substantial efforts and investment at all levels of government. At the city level, the Department of Social Services and Human Resources Administration must leverage Emergency Solutions Grants (ESG) and Community Development Block Grant dollars to help cover rent arrears for New Yorkers. Through the CARES Act, New York City received $330 million in ESG funds, allocated by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, to be used to prevent homelessness due to the pandemic. These flexible funds can and should be used to cover arrears for all tenants, regardless of immigration status. At the federal level, extending PUA through the duration of the economic crisis and providing substantial rental assistance to states and localities would provide a buffer for families who are still unable to make rent in the middle of this crisis.