Mar 12, 2021

Why Asian-American Poverty Doesn’t Get the Attention It Needs

Robin Hood is working to bring the AAPI community’s challenges to light.

By Christine Auyeung, Senior Program Officer | Young Adults and Jennifer Li, Manager | Development Operations and Kit Yong, Director | Human Capital

ABC Photo Illustration

The violence facing Asian American and Pacific Islanders in the U.S., though not new, has recently gained headlines and celebrity attention. According to NYPD data, New York City alone saw an 867% increase in racially motivated crimes against Asian Americans in 2020 compared to the year before.

What gets fewer headlines though, is the fact that even prior to the pandemic, Asian New Yorkers have been living in poverty, and that poverty among Asian Americans is the fastest-growing in the city. In New York City, the number of Asians living in poverty grew by 44 percent in the last decade and a half, from 170,000 to more than 245,000. The poverty rates for Asian-American communities are 15 to 25% higher than the city average.

So targeted violence and rapidly increasing poverty have become twin crises, threatening to push a community that has been historically invisible, and too often suffers its poverty in silence, even deeper into the shadows.

The term “Asian” is a monolith: Asians represent an incredibly diverse group of 48 countries speaking 2,000 languages. The mainstream narrative tends to describe this group as uniform, over-emphasizing higher-income Asians without acknowledging the wide-ranging income disparities throughout.

The income disparity among Asians is now wider than for any other racial group. It exists both between populations (Asian-American women are paid just 87 cents for every dollar paid to white, non-Hispanic men) and within Asian Americans, too (The Pew Research Center found in the U.S., Asians in the top 10% income bracket earned 10.7 times as much as Asians in the bottom 10%).

Hand-in-hand with the income gap is the Asian glass ceiling, or “bamboo ceiling,” defined as “a combination of individual, cultural, and organizational factors that impede their career progress.” Studies have shown that Asian Americans are the least likely group in the U.S. to be promoted to management across industries such as tech, banking, legal and accounting.

A 2017 report published by the Ascend Foundation, a group of pan-Asian accounting partners, found that while over 20% of the associates in many of the larger accounting firms were Asian-American, very few were being promoted to the partner level.

The problem exists at the service level, too: AAPI people represent 15% of New York City’s population, but only receive 1.4% of public social service contracts. And not all nationalities are represented equally — Chinese-American organizations receive more than 90% of public social service contracts. This means the incredibly diverse AAPI community is chronically underserved by philanthropy dollars.

Gathering data to evaluate the scope of the problem is a challenge, thanks to a high margin of error given the small population and wide diversity. Even in large surveys, limited English proficiency and high linguistic and ethnic diversity make it difficult to have a representative sample.

Robin Hood’s community partners are doing incredible work. The Chinese-American Planning Council promotes the social and economic empowerment of Chinese-American, immigrant, and low-income communities. In September, CPC’s Community Health Services program pivoted to create virtual workshops for over 600 young people, ranging in topics from managing college finances to mental health awareness. Robin Hood’s Mobility LABs initiative continues to partner with CPC to support their work in Flushing, Queens.

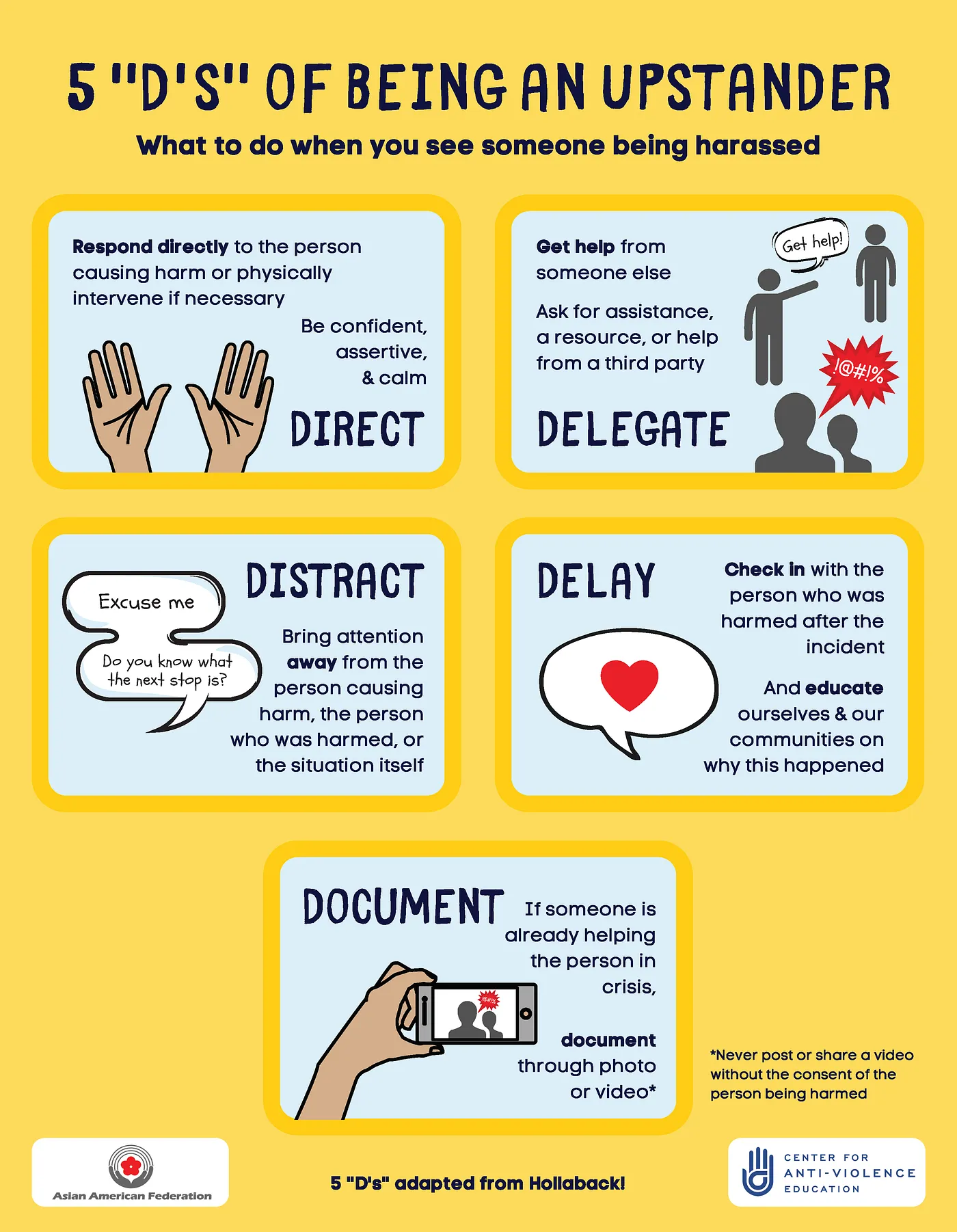

Among the many ways the Asian-American Federation has responded to the current crises facing the community is a set of multi-lingual anti-hate safety resources, created in collaboration with the Center for Anti-Violence Education. Their flyers, offered in five languages, teach people how to de-escalate threatening situations and defend themselves. They also empower onlookers with methods to safely intervene if they see someone else in danger.

Asian American Federation educational flyer

And, going forward, Robin Hood’s Power Fund will be addressing these inequities by continuing to elevate nonprofit leaders of color — including Asian-American leaders — to break through the barriers that prevent recovery from poverty in the communities they serve.

Internally, we’re assessing AAPI representation in our events such as No City Limits and Investors Conference.

Soon, the Poverty Tracker, Robin Hood’s joint venture with Columbia University’s Center on Poverty and Social Policy, will include a Mandarin-speaking sample in its long-term poverty research, which will be one of the few longitudinal research projects focused on Asian-American poverty in the United States.

Amplifying the voices of AAPI New Yorkers living in poverty is essential to bringing the community’s challenges to light. Invisibility simply isn’t an option anymore.